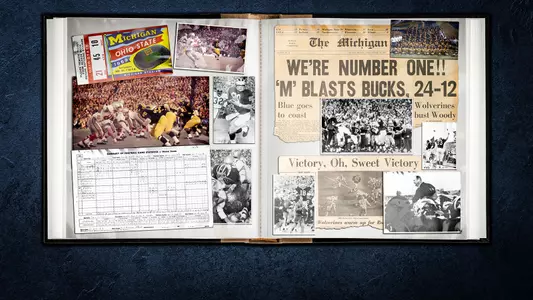

50th Anniversary: Recalling 1969 Upset of OSU Ahead of Another Big Game

11/26/2019 10:43:00 AM | Football, Features

By Steve Kornacki

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Fifty years have passed since Bo Schembechler's Wolverines dominated Ohio State and Woody Hayes in the upset that snowballed into a football dynasty for the Maize and Blue.

I wrote a 20th-anniversary piece on that 24-12 victory for the Detroit Free Press, and so many quoted in that story have gone on to what the late great voice of Michigan football, Bob Ufer, called "that football Valhalla in the sky." Tight end Jim Mandich, the co-captain and driving force, and fullback Garvie Craw, who scored two touchdowns, both died of cancer before they could retire. Bo left us when his heart gave out for good 37 years after his first heart attack on the eve of the Rose Bowl his team reached by taking down 17-point favorite Ohio State.

Schembechler won the first of 13 Big Ten titles in his 21 seasons at the University of Michigan, and the Wolverines made it 19 conference titles in the next 36 years.

"I was just a young whippersnapper then," Schembechler, who was 40 in 1969, told me in 1989. "I was struggling with that team (being 3-2 at midseason). But when we won, I knew it was big -- real big."

During the current decade, I wrote chapters on the greatest victory in the history of Wolverine football in two books: "Go Blue! Michigan's Greatest Football Stories" and "Miracle Moments in the History of Michigan Wolverines Football," which I co-authored with my son, Derek. Bo's youngest son, Shemy, wrote the foreword for the latter.

So, I've spent a great deal of time delving into that magical, sunny, cool, crisp, late-autumn afternoon at Michigan Stadium and the significance and special tales of what happened in that monumental game.

Bo Schembechler (left) and 1969 captain Jim Mandich

Odds are, this could be the last time I write about it to this extent.

So, what do I write? I've thought about it quite a bit. And I will share some of my favorite quotes from current Wolverine radio voices Dan Dierdorf and Jim Brandstatter -- both members of that team -- as well as Mandich, Craw, Reggie McKenzie, Glenn Doughty, Don Moorhead and Dick Caldarazzo.

However, let's start with just how connected this memorable group -- the "ground zero" unit for Bo's "The TEAM! The TEAM! The TEAM!" concept -- remains with Michigan football.

The surviving members of the '69 team will be honorary captains for the Saturday (Nov. 30) home game with Ohio State, and some eerie parallels exist between that matchup between the Wolverines and Buckeyes and this one.

In 1969, Michigan was ranked No. 12 and entered the game on a four-game winning streak, having crushed Big Ten opponents by a combined score of 178-22.

In 2019, the No. 10 Wolverines (9-2) are coming in with four consecutive wins, having outscored Notre Dame and three conference foes, 166-45.

"The setup for this year's game, with us celebrating the 50th anniversary of our game, is going to be so similar," said Tom Curtis, the All-America free safety. "When we beat them in '69, they were the defending national champions, having won 22 in a row (and ranked No. 1)."

Barry Pierson, a senior cornerback and the star of stars on Nov. 22, 1969, said of these Wolverines pursuing their own game to remember: "They're primed and ready to do that. All they've got to do is get it done. They haven't won for a long time (the last Michigan victory in the series was in 2011), Ohio State's on top, and we couldn't ask for anything better."

The returning 1969 players are scheduled to attend practice Friday before having dinner together. Mandich was the team captain, and Caldarazzo and Curtis will take his place at the pregame coin flip while their teammates stand between midfield and the sideline.

Another upset win for the Wolverines would make their reunion a smashing success.

"Oh, God, it'd be great," said Pierson. "Then they could talk about all of those guys for 50 more years."

Curtis added, "Winning again would be a fitting end to our 50th anniversary celebration."

There is so much to write about that classic game and what has transpired since. But what I'll focus upon as the meat of this piece is something I never have: Michigan's six interceptions that day.

There are so many reasons why that statistic should blow your mind.

First, there is the oft-quoted line from Hayes: "Three things happen when you pass, and two are bad." That line also gets credited to Darrell Royal, the legendary Texas coach from that same era of "Three yards and a cloud of dust" football. However, before passing away, Royal acknowledged Woody said it first.

Still, the Buckeyes threw 27 times that game, and those "bad" things happened on all but nine of them. Starter Rex Kern (6-of-17 with four interceptions and one touchdown pass) and Ron Maciejowski (3-for-10 with two pickoffs) were forced to throw after falling behind, 24-12, at halftime, and neither team scored in the second half.

"We'd prepared for that game for a year," said Curtis, "and Barry Pierson, who remains a great friend today, had the game of his life, making three interceptions. I intercepted two passes and Thom Darden intercepted one, and it was one of the greatest days of my life."

They didn't have a single pick-six but rather had a six-pick day.

"They couldn't run on us and so they had to throw," said Pierson. "But they had to try something, and I give them credit for trying."

Michigan received stout play from its linemen and linebackers to limit the Buckeyes in every way, but the Wolverine coaching staff also detected something OSU was doing to telegraph whether or not All-America fullback Jim Otis was going to be involved in the handoff.

Pierson said, "See, they were running the same offense we ran (the triple-option), and what happened was their wingback did not go in motion when they were going to give it to Otis. And when he went in motion, we didn't have to watch Otis because the quarterback was either going to keep it or pitch it.

"So, that gave us a big-time advantage."

Curtis said, "Our preparation started in spring ball, nine months before we played the game, because we'd gotten beaten in Columbus in Bump Elliott's last game, 50-14, in 1968. Then Bo came in and he pointed to that game immediately, and when we were preparing during the week for game opponents, he'd throw in something for the Ohio State game."

Barry Pierson's 60-yard punt return, aided by blocking from Bruce Elliott (21), set up Michigan's third touchdown.

It turned out that Ohio State -- which had taken a lead of at least 21-0 in every game that season before an opponent scored -- could not adjust to beat Michigan by throwing the ball.

Or perhaps it was that the Wolverines were simply a great, great pass-defending unit. They had All-America middle guard Henry Hill spearheading the pass rush and some real ballhawks in the secondary.

Curtis made the last two of his 25 career interceptions to set a Michigan career record that probably will never fall, having withstood Heisman Trophy winner Charles Woodson, who had 18.

"Tom Curtis has never gotten enough credit for what he did here at Michigan as far as interceptions," said Bruce Elliott, a sophomore on the 1969 team and nephew of Bump. "I've never seen a better pair of hands. That guy could catch anything, anywhere. And his anticipation was great. He wasn't a really fast guy, but he was a great athlete. He had a knack to anticipate that was amazing. He just knew where the ball was going -- I think before the quarterback even did. He knew where to be to have a chance to intercept or make a breakup."

Henry Hill (39)

Lineman Dan Dierdorf (72) celebrates quarterback Don Moorhead's touchdown run

Pierson made three of his four career interceptions that day. He said the Buckeyes, like many teams of that era, tended to throw more at short-side cornerbacks, and it made sense not to throw Curtis' way.

"I got one because I chased a guy and went underneath him and intercepted it," said Pierson. "On the third one, we were playing zone, and he threw into the zone and I went quite a ways to intercept it.

"I blew a couple of other ones, which is really interesting. They were down-and-outs (routes) and I dove for them. So, I had a chance at a couple more. And I always tell Curtis that he stole one from me (laughter). I could've had a banner day."

I mentioned to Pierson that he did have a banner day but allowed that it could've been a bigger banner.

"I mean, I had a good day," said Pierson, "but the whole team was sensational that day -- offensively and defensively. They weren't going to beat us. That's all there was to it."

Pierson also made an electrifying play, a 60-yard punt return. The pride of St. Ignace in Michigan's Upper Peninsula fielded the kick near the right hashmark and ended up using those hashes as his trail to glory. He zigged and zagged inside and outside those marks ever so slightly before being taken down at the three-yard line, and he ran triumphantly to the sideline, where assistant coach Frank Maloney hugged him.

"We had an interesting punt return (strategy) because I had more yardage than anyone in the history of Michigan football in one season up to that time," said Pierson, who had 19 returns for 300 yards (15.8 average) in 1969 and had a 51-yard punt return touchdown against Wisconsin that season.

"But when the teams came down after us, they were out of control, four or five of them. We didn't block them. It was up to myself or Curtis to avoid those guys, and then we had all our blockers (downfield). We were set up for long returns that way, and it was a nice punt return. I was weaving all over and got down in there, and Curtis waved me to go his way. I went the other way (laughter) and the guy got me from behind."

Pierson admitted that Curtis' "way might have been better" after all.

Elliott, who blocked in front of Pierson at one point on the return, said, "Barry was just running by everyone and had that great return. Those of us rushing the kick were down there trying to throw blocks, trying to help him out. I'm not sure if I ever told Barry this, but he was tackled at the three-yard line, and I am going to tell him this time (at the reunion), 'If you just followed my block, you would've scored!' But Barry did set the standard for punt returns. He was on fire and was a real threat."

That long return set up Michigan's third and final touchdown, a two-yard run by quarterback Moorhead. Dierdorf hugged Moorhead with great joy after that play, and the junior quarterback had quite a day. He completed 10-of-20 passes for 108 yards and ran 17 times for 67 yards. Only Billy Taylor, with 84 yards on 23 carries, had more rushing yards for the Wolverines that day.

Don Moorhead (27) quarterbacked the Wolverines to victory.

Billy Taylor (42) was Michigan's leading rusher in the game.

Both of Curtis' picks came in the first half, giving him eight for the season.

"The second one was one of the last plays of the first half," said Curtis, whose 10 interceptions in 1968 remain the program's single-season record. "I never scored a touchdown intercepting a ball at Michigan even though I had 25, and I set the record for return yardage (with 431 yards).

"Rex Kern was the Ohio State quarterback, and I played with him two years later on the Baltimore Colts. We always laughed about it, and he'd say, 'Yeah, I threw you the balls!'"

Two years later, Thom Darden had a two-pick game against Ohio State in 1971.

Darden, then a sophomore, made the other interception. He went on to make 45 of them in the NFL after the Cleveland Browns made him a first-round draft pick, and he was a three-time All-Pro. Schembechler and his coaches came up with the "Wolfman" name for Darden's safety position, and he could sure make things hairy for quarterbacks.

"Thom was an outstanding player," said Curtis. "He had size and was just an unbelievable hitter, a great athlete. The 'Wolfman' was a hybrid strong safety. Thom had two more years and then did great things in the NFL."

Elliott said, "Thom also had great anticipation on passes."

Curtis said all four starters in the secondary, which included senior cornerback Brian Healy and also nickel back Elliott, played quarterback in high school.

"Playing quarterback in high school really played into the anticipation we all had in the secondary," said Elliott, who had a 40-yard interception return for a touchdown at Illinois in 1969 for a triumphant return to his hometown of Champaign. "I think that was a big factor in all those interceptions along with just good pass defense in general.

"I played a lot of downs in the Ohio State game because they were passing so much and I was a nickel back. Playing in the secondary and seeing all those interceptions, I just couldn't believe it.

"That's what was so great about our defense. We had the down linemen like Henry Hill and linebackers that were hustling so much. Since we had them down like we did, they had to start passing more, and that was not quite their comfort zone."

Tom Curtis, with linebacker Marty Huff (70), returns one of his two interceptions against the Buckeyes.

Two other important elements in the game were payback and emotion. The Wolverines had lost, 50-14, to the Buckeyes in 1968, when Hayes opted to go for two points on the final touchdown. The seniors from that team were in tears afterward, and Mandich promised them Michigan would win for them in 1969. Schembechler put No. 50 on the scout team members, lockers and bed sheets entering the showers and bathrooms.

"Coming out on the field before that game was really stunning," said Elliott. "When we came out of the locker room and ran out, we were all jumping around, getting ready. Everybody was really pumped. Ohio State came out and they just kind of sauntered out onto the field, ho-hum, like they were getting ready for an intrasquad scrimmage.

"It was a striking difference right from the beginning. And the coaches did such a good job of preparing us and convincing us that we were going to win. We didn't have a doubt, and it wasn't wishful thinking. It was the best coaching job I ever saw in my life."

Curtis said that as great as the interceptions were, his favorite play in the game "was sticking Jim Otis on a third-and-one."

Curtis added that one memory of that game is clearer than most:

"I can remember it so vividly, standing on the sidelines, watching the seconds click off the clock: 12, 11, 10. And I look next to me and one of my best friends from high school (in Aurora, Ohio), Geoff Jewett, who had come to the game with friends, was standing next to me on the sideline. I looked at him and said, 'WHAT the hell are you doing here?' And of course he'd been drinking all day, and he jumped over the wall and avoided security. I'll never forget that. He lives out in California and we're still very good friends. We always laugh about it."

Everyone in Ann Arbor, including the conquering heroes, celebrated.

"We partied for about one week after that game," said Pierson. "We were all pretty spent after that game."

He said they'd gather sometimes at the Pretzel Bell, Mandich's apartment or whatever worked out. Mandich and Curtis were roommates, too.

They'll have a get-together Friday night in Ann Arbor, and it will be like old times. But how will it also be different from when they got together in their college days?

"I don't know," said Pierson. "I think we're all telling lies now. But we'll still have a pretty good time. We'll talk a little football and ask about what our families are doing. We've had a ton of guys who have passed away, though. I looked at the front row of the team picture and eight guys are gone."

Pierson, who was a graduate assistant for Schembechler for three seasons, coached several high school football teams over five decades and was a teacher for six years. All three of his sons -- Charlie (Ferris State), Chase (University of Chicago) and Zach (Northern Michigan) -- played college football and he has a daughter, Hayley, and two grandchildren, Lucas and Maddie. Barry also bought and sold fish commercially as a broker and is now retired in St. Ignace. His wife, Cindy, boats across the straits daily to operate Thunderbird Gifts on picturesque Mackinac Island.

Elliott started in Michigan's secondary as a junior and senior and then went to law school at Miami, where his father, Pete, was the football coach and then an athletic director for the Hurricanes. Pete and his brother, Bump, were All-Americans in the "Mad Magicians" offensive backfields that produced a pair of national championships for Michigan in 1947 and 1948. Bruce, who came to Ann Arbor to play for Bump in 1968, admired that Schembechler always credited his uncle for "leaving the cupboard full with high-character guys" after replacing him as head coach. Bruce was a graduate assistant on the football teams while in law school and also at Tennessee. He wanted to coach but said he "never regretted" becoming an attorney.

He also has another great reason to remember Nov. 22, 1969.

"The very first date me and Cheryl (also a Michigan student) had was the night of the upset win over Ohio State," said Bruce. "I asked her out the week before the game, and then told her I engineered the win to impress her."

They were married and had two daughters who both played in Final Fours for Division I field hockey teams -- Jennifer at Princeton and Courtney at Duke. Jennifer has a son, Peter Catanese, and is expecting a second son in December.

Curtis played two years with the Baltimore Colts and won Super Bowl V with Johnny Unitas and Co. before moving into publishing. Curtis once owned the Football News and four NFL team publications, and he still has the weekly River Cities Gazette in Miami Springs, Florida, and Steelers Digest and has "no plans to retire." He has three children: Tammi, Brad and Matthew (who has a son, Matthew Jr.), and the boys were good high school baseball players. He also maintains a home just down the road from Michigan Stadium in Saline and spends much of the summer around the family of his daughter and Jason Carr, a former Wolverine quarterback.

Jason is the son of Michigan coaching great Lloyd Carr, and Tom said his daughter spotted Jason's photo in a football game program when she was visiting campus and pointed to it, saying, "I like this guy right here."

Tom Curtis (maize hat) and Lloyd Carr (blue hat) with the late Chad Carr (in father Jason's arms) and family before the 2015 Oregon State game

Tom said it took them several years to begin dating. They got married and had three sons, CJ (an eighth-grade quarterback), Tommy and Chad, the youngest. Chad died of a rare brain cancer Nov. 23, 2015. He was five years old.

The #ChadTough Foundation, which has raised millions to fight pediatric cancer, was named for the grandson of two College Football Hall of Famers and has carried on the great fight the young boy showed in battling to the end.

"It's no journey any parent or grandparent would want to go through," said Curtis. "My daughter, Tammi, is so strong, and she took everyone through that journey and has continued. But I can't really talk about it."

Grandpa Tom got choked up and had to pause for a few seconds.

"The hurt never goes away," he added.

Curtis noted of the 2015 Wolverines: "And they all came to the service the day after they lost to Ohio State. It was so touching, and they all got behind it with the orange hair and moustache."

Orange was Chad's favorite color, and Wolverine defensive end star Chase Winovich dyed his hair orange for the Outback Bowl two years ago. Defensive coordinator Don Brown dyed his moustache, and other players followed the challenge in order to raise money for #ChadTough.

The '69 team members will talk this weekend about their families, careers and the football team they still love dearly. And they'll continue cherishing an upset that bonded them for life.

"We'll talk about the significance of that day in each of our lives," said Curtis. "That's why it's going to be so significant, and it's great Michigan is honoring us on the field."

Elliott said, "That win jump-started the program, and not only for the next year and the years after that, but for 20 more years under Bo and then when Mo (Gary Moeller, an assistant on that 1969 team) and Lloyd (Carr) were there as head coaches.

"It changed the whole nature of the program and the expectations and the mindset of everyone. It was nothing short of phenomenal."

Elliott, one of the reunion organizers, expects 60 to 70 to return.

"And now it's amazing that so many guys are coming back," said Elliott. "I look forward to seeing Barry Pierson and Tom Curtis and everyone there, but I don't think Brian Healy can make it. It'll be fun catching up. They were great players and great leaders -- all the seniors on that team were extraordinary."

Together, those Wolverines changed the narrative, changed a program and changed history.

Watch -- Brothers, Teammates, Champions

I've interviewed quite a few of the '69 Michigan players over the last 30 years. Pieced together, some of my favorite comments from those conversations give a first-hand account of how the Wolverines pulled off one of college football's biggest upsets in a game that left an indelible mark on the participants, reignited a fierce rivalry, and shaped the program's success for years to come.

Tailback Glenn Doughty recalled the pregame speech and compared Schembechler to a "symphony conductor" building to the crescendo:

"Bo said, 'How dare they say this is the Team of the Century? We're the Team of the Century! Before he could finish, someone shouted, 'Let's go, Bo!' and the place went wild. Guys were throwing chairs and beating lockers down. It was like an earthquake, and we had to leave for our own safety.

"We were David going after Goliath, but not with a rock. We had a nuclear bomb. We were on a mission to kick ass. We were like piranhas, and Ohio State was the little fish. We could not wait to eat those little suckers alive. Psychologists would say we couldn't play on that emotion all day, but it lasted through the entire game and into the parties that night."

Wolverines All-America offensive guard Reggie McKenzie, a future College Football Hall of Famer, remembered the fire they all had in their bellies:

"When somebody asked Woody why he went for two (in 1968), he said, 'Because I couldn't go for three.' We said, '(Blank) you!' So, we made it a point to remember that. (All-America tight end and co-captain) Jim Mandich promised those seniors that we would beat Ohio State the next year, and we did. There were tears."

Reggie McKenzie celebrates in the locker room

Mandich recalled the chant after the team won at Iowa in the previous game: "WE WANT OHIO STATE!" Offensive guard Dick Caldarazzo said the coaching staff was leery of their enthusiasm coming too soon:

"They worked us hard because they thought we were too high, too fast. But we said, 'Don't worry, we'll get higher.'"

Jim Brandstatter, the long-time radio voice of the Wolverines and an offensive tackle on that team, paid a special tribute to game star Pierson:

"In Michigan history, I don't think there was ever a bigger game played than by Barry Pierson in the Ohio State game of 1969. He played in the backfield with an All-American in Tom Curtis, and we had Thom Darden, a very highly regarded sophomore. In the biggest game on the biggest stage, Barry Pierson outdid them all. He didn't have the name recognition or reputation, but he was the best player on the field on that day. Amidst (OSU's) Jack Tatum and Rex Kern and Jim Otis, and (Michigan's) Dan Dierdorf and Jim Mandich and Tom Curtis, all those great names and others, Barry Pierson had one of the greatest impacts in Michigan history in that game.

"We were all fired up, that was the thing. You don't pull that kind of upset with one guy having a great game. You do it with all of you having the great game, and all of you being prepared, and all of you on top of your game. And we did that that day, but Barry just had one of those days. Everything slowed down and Barry was in the right place at the right time at every occasion, and when the opportunity came, he took it and exploited it. He didn't shy away from it. We were all in that same mindset, that we were going to win this game whatever it took. He made the plays, though."

Mandich, who died of cancer in 2011, told me in 1989: "It was very pure and real. I had a lot of emotional games in the pros (four Super Bowls with Miami and Pittsburgh), but what I always come back to in the meanderings of my mind is that game."

Garvie Craw (left) and Jim Mandich

That game featured off-the-charts emotion from start to finish.

"From the beginning to the end of that game," said McKenzie, "that place was the loudest ever. I don't know that anyone ever sat down. It was electric; you could feel it in the air. And after the game, the fans came down and tore down the goal posts.

"If you were there, you will never forget it. Nobody was supposed to beat Ohio State."

Fullback Garvie Craw, who died of cancer in 2007 at 59, said 30 years ago:

"Bo said he was closer to that first group because he put us through a lot. We had to listen to all his B.S. But, you know, he was right. Everything he said was right."

Quarterback Don Moorhead, who outplayed Buckeye All-America quarterback Rex Kern that day, noted of their legacy and Michigan's run of Big Ten championships:

"It may have taken longer if Ohio State had won. It may have been years before Bo could've gotten kids excited about coming here. But after that, Bo was known to everyone."

All-America offensive tackle and future college and pro football hall of famer Dan Dierdorf put it all into perspective:

"If I could re-create any one day, it would be that one. It just didn't get any better than that."